Inna Nam Brady* | 1 Regent J. Glob. Just. & Pub. Pol. 227 (2015)

INTRODUCTION

Kazakhstan is a predominantly Muslim country. However, the Constitution of Kazakhstan has proclaimed that Kazakhstan is a secular state.[1] Article 14 of the Constitution states a guarantee that “no one shall be subject to any discrimination for reasons of. . . attitude towards religion.”[2] Freedom of conscience and freedom of forming associations are guaranteed in articles 22 and 23, and censorship is prohibited by article 20.[3]

However, on October 11, 2011, the President of Kazakhstan signed the Law on Religious Activity and Religious Associations (the Law), replacing the former law on religious freedom.[4] The Law has been criticized by international human rights activists and organizations as infringing religious freedom because it requires registration, restricts religious materials, and prohibits religious activities in public places.[5] For example, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) in its Annual Report for 2013 called the Law “repressive” and the cause of “a sharp drop in the number of registered religious groups in 2012.”[6] The USCIRF for the first time classified Kazakhstan as a tier-2 country.[7]

The Director of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), Ambassador Janez Lenarčič, expressed concern about the Law saying, “[t]he law appears to unnecessarily restrict the freedom of religion or belief and is poised to limit the exercise of this freedom in Kazakhstan.”[8]

The criticism of the Law is not baseless. A sharp drop in the number of registered religious groups took place after the new religious law went into effect.[9] The official statistics depict the drop as approximately one third.[10] By October 2012, when a year-long re-registration period ended, the number of registered religious organizations fell from 4,551 to 3,088 religious communities, from forty-six to seventeen religious confessions, and from twenty-eight to thirteen religious educational institutions.[11]

Kayrat Lama-Sharif, the then head of the Agency for Religious Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan (ARARK), said that among 666 protestant Christian groups, 462 could not re-register, meaning that 69% of them were closed.[12] He explained the drop by claiming that many of the previously registered groups existed on paper, but not in fact.[13]

Lama-Sharif’s statement that the drop was caused by the closure of non-existent associations is disputable, as discussed later in this article. The requirements of the Law did influence the drop in the number of registered Christian communities as well as other aspects of religious freedom; but it must be noted that this article is not intended to focus on how to “argue” with the lawmakers. Rather, the goal of this research is to give an overview of the Law’s impact on Christian activities in Kazakhstan as well as suggestions for how Christians can legally work within the framework of the Law.

There are three major spheres that were affected by the Law: (1) the registration of religious associations and missionaries; (2) restrictions on the use of religious literature and other religious materials; and (3) the places and mode of religious activities. These three spheres will be discussed below.

REGISTRATION

A. The Requirement of a Minimum Number of Founders

The first step to start with is registration. Religious activities of non-registered associations are prohibited.[14] All emerging communities must be registered, and all existing communities were required to re-register within one year from the enactment of the Law.[15] The communities that failed to re-register within one year were to be liquidated through the court.[16]

The requirement of registration is not something new. The old 1992 law also required registration, but the Law took it one step further; it included a more detailed description of required documents[17] and increased the minimum number of founding members.[18] The new minimum number is now fifty members in order to be eligible for the registration of a local association,[19] 500 members are required for the registration of a regional association, and 5,000 members are required for the registration of a national association.[20]

According to the USCIRF, religious groups have described the re-registration process as “complex,” “burdensome,” “arbitrary,” “unnecessary,” and “expensive.”[21] Lama-Sharif, the head of ARARK at the time of the Law’s implementation, said that the Law treats all religions evenly and emphasizes the “secular character of the State.”[22] It is true that the Law sets a high threshold of registration for all religions, be it Islam, Christianity, Judaism, or Hinduism. However, the impact of the Law draws a vivid line between those groups that are stronger in number and the minorities, as is obvious from the statistics.

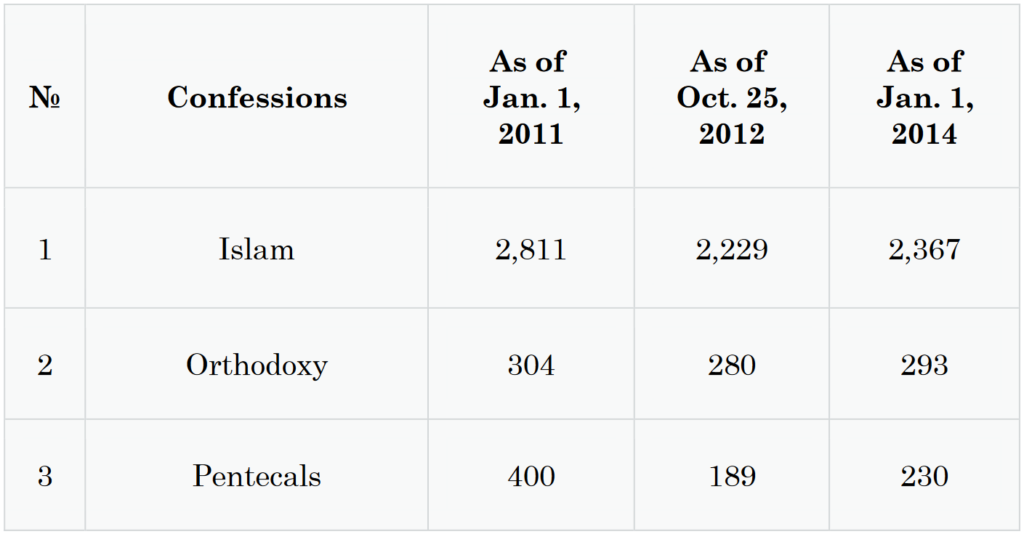

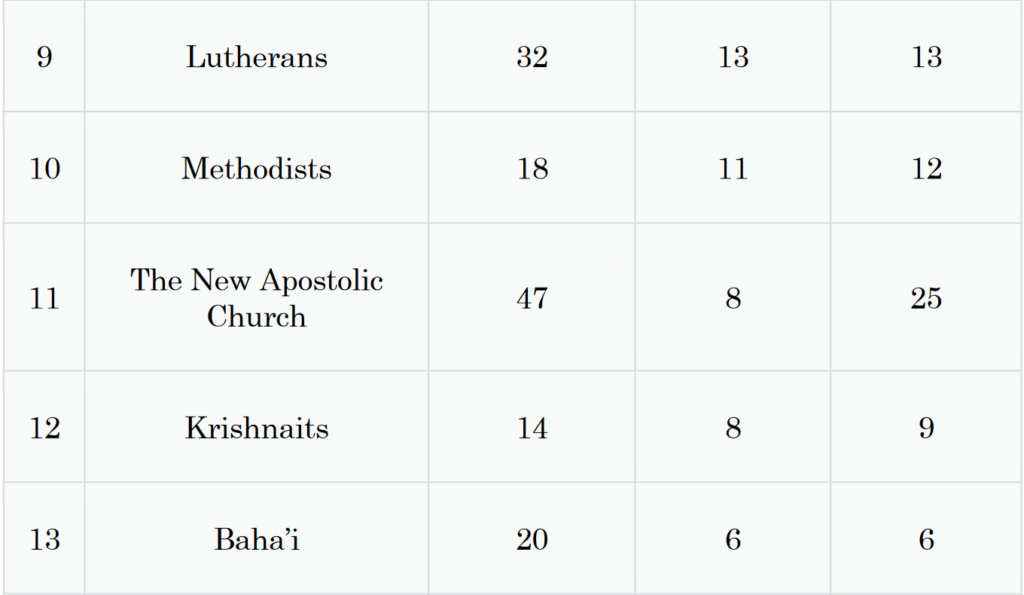

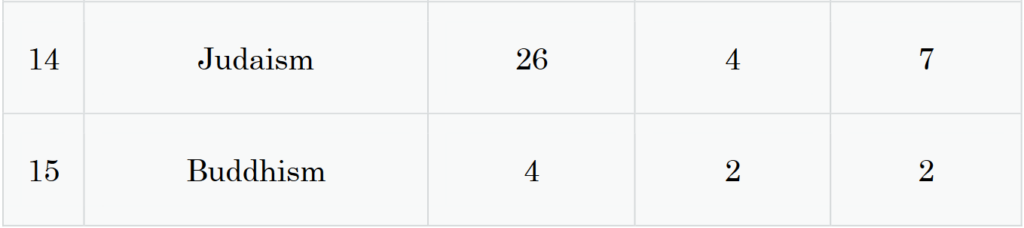

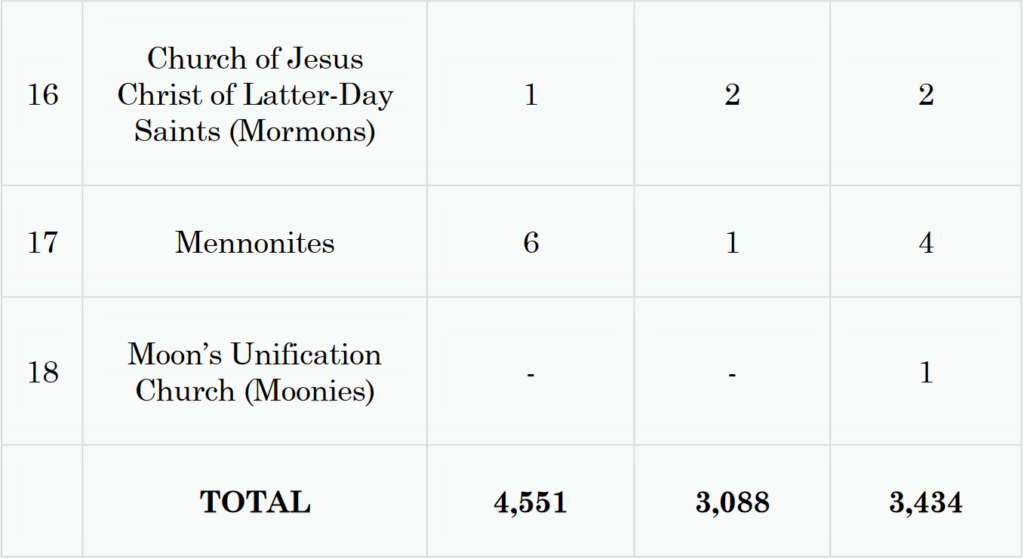

Ninel Fokina, the head of the Helsinki Committee in Almaty, a nongovernmental human rights organization and member of International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights, commented on the Law stating, “[a]ll will be affected, but especially minorities like Catholics, Lutherans, and Jews. It will be difficult for them to gather fifty people for the registration.”[23] The statistics speak for themselves. According to ARARK’s official web site, as of January 1, 2015, there were 3,514 registered religious organizations of eighteen confessions.[24] This number is almost one third less than the number before the Law was enacted (4,551 associations of forty-six confessions).[25] As the table below shows, Pentecostals, Baptists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, the New Apostolic Church, Baha’i, Judaism, Buddhism, and Mennonites dropped in number by a rate more than half after the re-registration deadline (those confessions are highlighted in the chart below).

Table 1: Religious Organizations in the Republic of Kazakhstan[26]

As stated in the introduction, Lama-Sharif, the former head of ARARK, explained the drop by reasoning that many of the previously registered groups existed only on paper, but not in fact.[27] However, the requirement of at least fifty members as a prerequisite for registration has apparently played a significant role in the post re-registration statistics.[28] The imposition of this restriction favors associations that are strong in numbers, and at the same time makes the registration of new associations difficult.

To give an illustration, a usual way of planting churches is a “pioneer model”[29] where a church is started as a small independent gathering of five to ten people or as a house church and then it grows in number. In view of the minimum fifty founders requirement, this kind of church planting method is strongly disfavored and greatly inhibited.

Nonetheless, there are some ways to overcome such difficulties. For example, one of the approaches could be an “adoption model”[30] where a small gathering of less than fifty adult members is held under the name of an already registered church. The registered church in this way would have full responsibility for all religious activities of the “adopted” smaller community. Additionally, the plant church’s property or premises would need to be registered under the name of the “adopting” church because the Law requires religious activities to be held only in such places.[31]

Continue Reading in the Full PDF

- CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN, 1995, art. 1. ↩︎

- Id. art. 14. ↩︎

- Id. arts. 20, 22–23. ↩︎

- Zakon Respubliki Kazakhstan o Religioznoi Deiatel’nosti i Religioznykh Obieedineniiakh [The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Religious Activity and Religious Associations] (Oct. 11, 2011), art. 3, § 11, available at http://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31067690 [hereinafter the Law]. ↩︎

- Id. arts. 7–9, 15. ↩︎

- United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Annual Report 2013, U.S. COMMISSION ON INT’L RELIGIOUS FREEDOM, 243–44 (Apr. 2013), http://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/resources/2013%20USCIRF%20Annual%20Report%20(2).pdf [hereinafter USCIRF Annual Report 2013]. ↩︎

- Id. at 242. To be placed on Tier-2, USCIRF must find that the violations of religious freedom are increasing, particularly severe, and at least one of three elements of the “systematic, ongoing, egregious” standard is met. Id. at 3. ↩︎

- Thomas Rymer, OSCE Human Rights Chief Expresses Concern over Restrictions in Kazakhstan’s New Religion Law, OSCE (Sept. 29, 2011), http://www.osce.org/odihr/83191. ↩︎

- Chislo Religioznykh Obieedinenii v RK Sokratilos’ na 32% Posle Pereregistratsii – Lama Sharif [The Number of Religious Associations in RK Has Decreased for 32% After the Re-registration – Lama Sharif], NOVOSTI-KAZAKHSTAN, AGENTSTVO MEZHDUNARODNOI INVORMATSII [NEWS -KAZAKHSTAN, AGENCY OF INT’L INFO.] (Oct. 25, 2012), http://newskaz.ru/society/20121025/4179139.html [hereinafter News-Kazakhstan]. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- V Kazakhstane Podschitali Kolichestvo Religioznykh Obieedinenii [The Number of Religious Associations Was Counted in Kazakhstan], NOVOSTIGAZETA.KZ (May 15, 2013, 2:34 PM), http://news.gazeta.kz/news/v-kazakhstane-podschitali-kolichestvo-religioznykh-obedinenijj-newsID381077.html. ↩︎

- NEWS-KAZAKHSTAN, supra note 9. ↩︎

- Dimmukhammed Kalikulov, Kazakhstan Uslozhniaet Registratsiiu Religioznykh Grupp [Kazakhstan Makes Registration of Religious Groups More Complicated], BBC RUSSKAIA SLUZHBA [BBC RUSSIAN SERVICE ] (Sept. 29, 2011, 7:33 PM), http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/international/2011/09/110929_religious_law_kazakhstan. ↩︎

- Zakon Respubliki Kazakhstan o Religioznoi Deiatel’nosti i Religioznykh Obieedineniiakh [The Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Religious Activity and Religious Associations] (Oct. 11, 2011), art. 3, § 11, available at http://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=31067690 [hereinafter the Law]. ↩︎

- Id. art. 24, § 2. ↩︎

- Id. art. 24, § 3. ↩︎

- Id. art. 15, § 3 (stating seven documents required for the registration of religious association: (1) bylaws of the religious association signed by the leader of the association; (2) minutes of the initial meeting, (3) the list of the founding members; (4) a confirmation of the association’s location, (5) religious materials about the history and theological features of the denomination, including the description of its religious activities; (6) registration fee; and (7) decision on the election of a leader or approval of the appointment by the ARARK if the leader was appointed by a foreign religious center). ↩︎

- Id.; cf. Zakon Respubliki Kazakhstan o Svobode Veroispovedaniia i Religioznykh Obiiedineniiakh [Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan on Religious Freedom and Religious Associations] (Jan. 15, 1992), art. 9, available at http://www.pavlodar.com/zakon/?dok=00160&al=all [hereinafter Religious Freedom and Association Law]. Compared to the old law’s requirement of only ten founding members, the Law’s minimum number is fifty adult members. ↩︎

- The Law, supra note 14, art. 12, § 2. ↩︎

- Id. art. 12, §§ 3–4. ↩︎

- USCIRF Annual Report 2013, supra note 6, at 244. ↩︎

- Kalikulov, supra note 13. ↩︎

- See id. ↩︎

- Religious Associations, COMMITTEE FOR RELIGIOUS AFF. OF THE MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND SPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN, http://www.din.gov.kz/rus/religioznye_obedineniya/?cid=0&rid=1715 (last visited Mar. 18, 2015). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Kalikulov, supra note 13. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- The term “pioneer model” here is used purely for the purpose of convenience, not in a missiological context. ↩︎

- The term “adoption model” here is used purely for the purpose of convenience, not in a missiological context. ↩︎

- The Law, supra note 14, art. 7, § 2. ↩︎

* Inna Nam Brady was born and raised in Kazakhstan. She received her Specialist in Jurisprudence degree from L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University in Kazakhstan, M.Div and Th.M from Korea Nazarene University, and graduated Summa Cum Laude from Handong International Law School in 2014.